For me, one of the compensations for not living by the sea is the theatres in London. In the years pre-Covid, I usually spent my weekends at one of the theatres or concert halls in the West End or beyond, and there has been many a weekday when I have queued online for ‘priority booking’ as the box office opened and paid for certain performances for up to a year in advance.

On 15th March 2020, I trekked off to the National Theatre for an epic eight-hour play, The Seven Streams of the River Ota – a Robert Lepage masterpiece. There was a two-hour interval between the afternoon’s first half and the evening’s four-hour finale. I arrived with my takeaway dinner beautifully packaged from Corbyn & King’s The Delaunay Counter. Inside the theatre, there was a sense of nervousness – we did not yet know about mask wearing, or keeping our distance, and I did wonder if I was mad to be sitting in a packed theatre?

And then lockdown happened just a few days later. Theatre lights all over the UK went down, and there was darkness in an industry that has been part of the fabric of this country since the 1500s.

Eighteen months later, and theatres have been open for some weeks now. Going back again has been a joy – a real highlight of my summer.

With this in mind, I thought it the perfect time to catch up with Robert Fox, the world-renowned producer, and someone I have always wanted to interview. Robert has produced over 50 plays in the West End and 17 on Broadway. He is behind some of theatre, film and TV’s best-known productions, including the David Bowie musical Lazarus, the Netflix drama The Crown and my favourite of all, The Lady in the Van with Maggie Smith. Catching up on Zoom, we discussed the role theatre plays in cities, its contribution to our economy and whether this past chapter will kickstart lasting change in the industry.

Unsurprisingly, Robert was born into the theatre. “My dad was a producer when I was young, and an agent once I got a bit older” he told me. “So I was surrounded by writers, actors, producers and directors for my entire adolescence.” Certainly, this love of the arts runs in the family: Robert’s older brothers are the BAFTA-winning actors James and Edward Fox, and he is uncle to actors Emilia and Jack Fox. His grandfather was playwright Frederick Lonsdale and his mother an actress and author.

Over the past eighteen months or so, we’ve seen theatres close their doors, adapt to provide entertainment to audiences from home, flex to reopen with social distancing restrictions, close again and now finally reopen – hopefully for good. Around the world, from London’s West End and New York’s Broadway to small regional theatres, communities and local authorities have been reminded of the role that theatres play within cities.

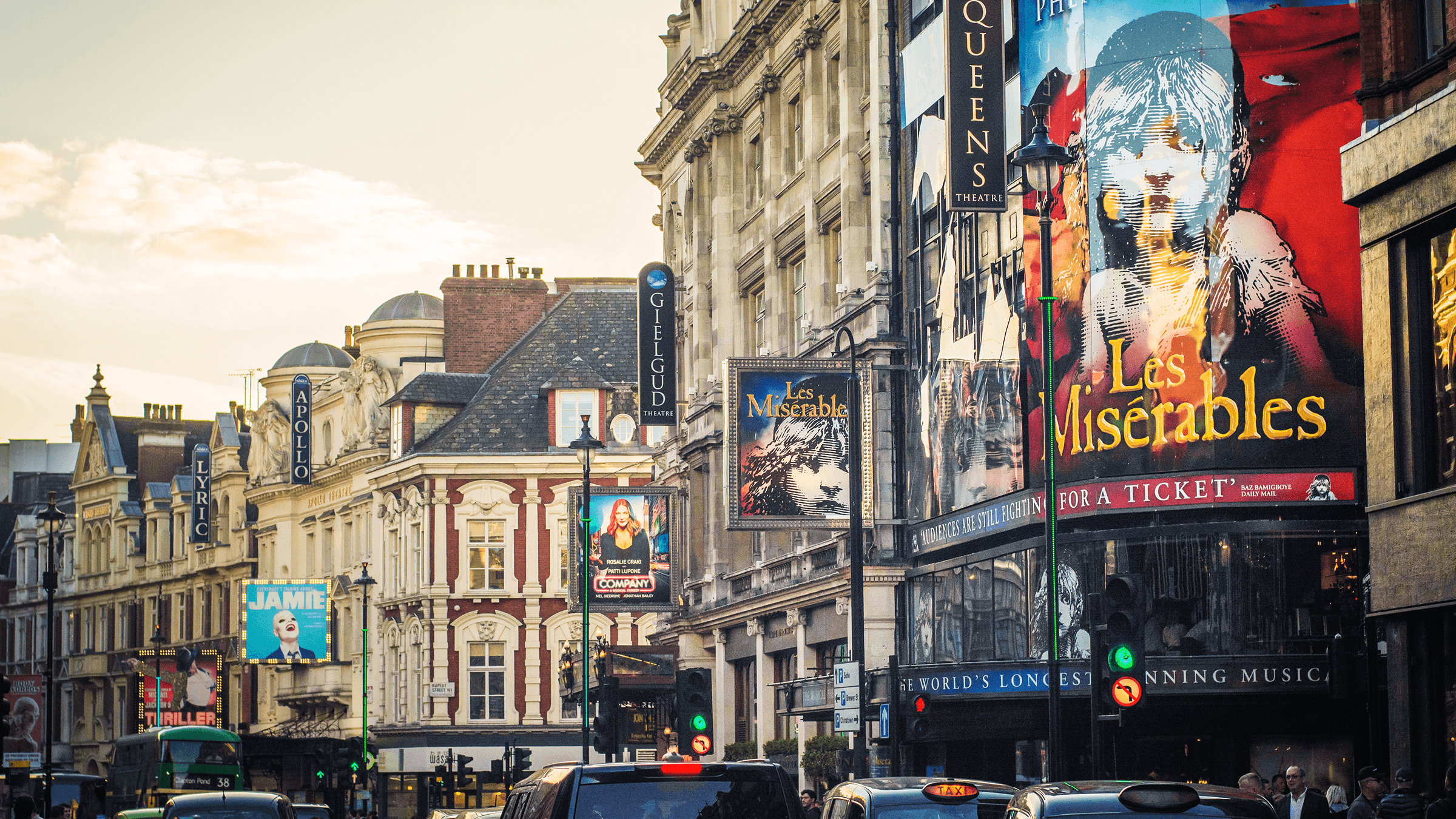

“Financially, the importance of commercial theatre cannot go understated,” Robert told me. “In London, for example, the West End provides a huge amount of revenue for the government through VAT from successful productions. But it’s also a beacon which draws people into the capital. Those who travel to London to see a musical or a play will then use cafes, restaurants, hotels and public transport, contributing even more to our economy. And then of course, there are all the self-employed people: set builders, costume designers, lighting experts, musicians, sound technicians, ushers, make-up artists, just to name a few.” Indeed, at the last count from the Arts Council, arts and culture were found to contribute £10.8bn every year to the UK – surpassing agriculture’s contribution.

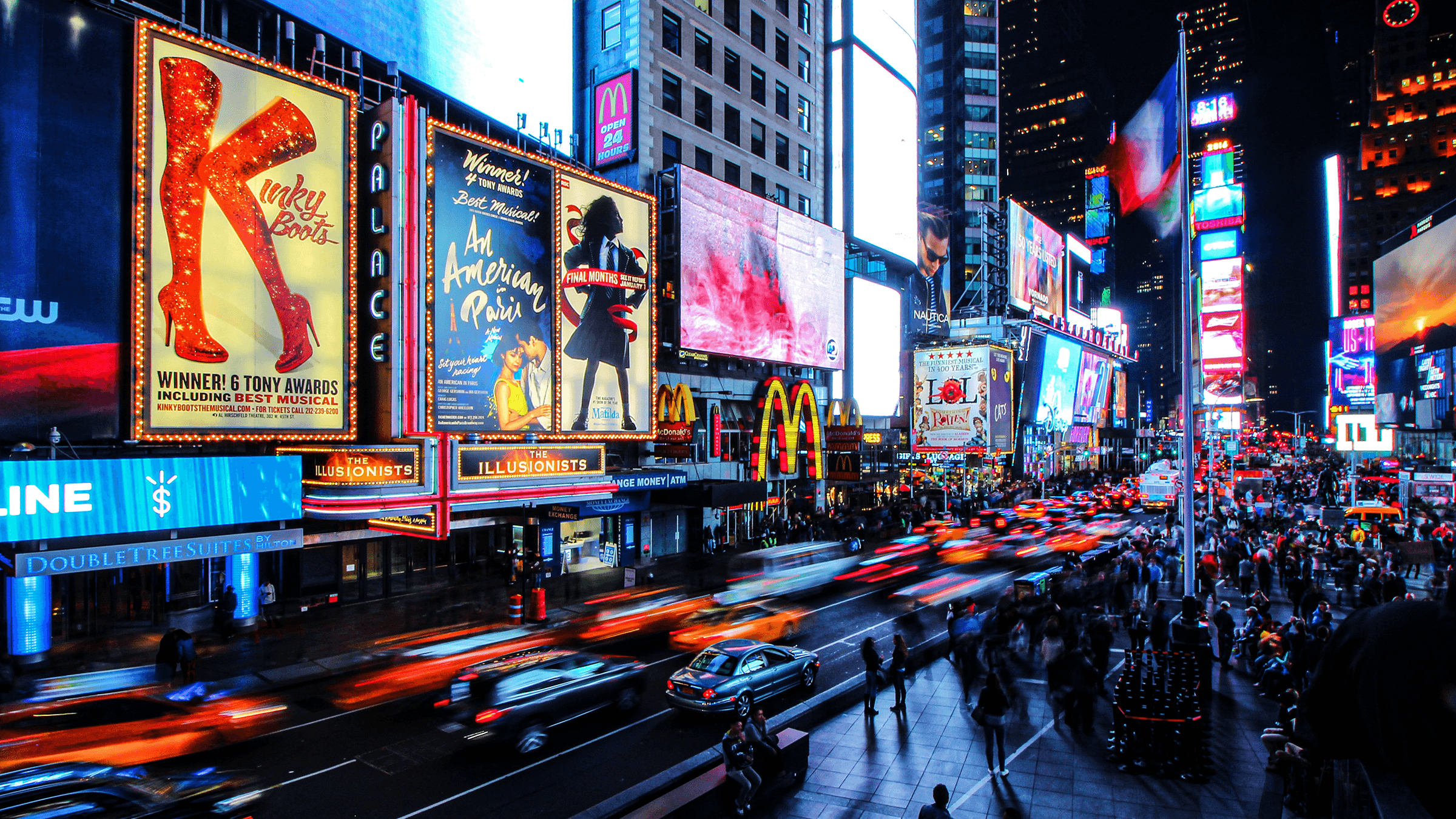

“Theatres also breathe life into city centres. Without them, there are real gaps in places like London or New York.”

“Theatres also breathe life into city centres,” Robert continued, “without them, there are real gaps in places like London or New York.” We all remember walking through city centres at the height of lockdown, and I for one am certainly glad that London’s theatreland is buzzing again.

Since the start of the pandemic, we’ve witnessed theatres reinvent themselves in a bid to keep their audiences engaged through different iterations of lockdown restrictions. As early as April 2020, the award-winning theatre company Headlong announced Unprecedented: Real Time Theatre from a State of Isolation, a series of 12 plays rehearsed and performed online; last summer, American playwright Richard Nelson virtually released his play What Do We Need to Talk About which was enacted via Zoom; and in December, the National Theatre launched National Theatre At Home, a dedicated streaming service giving users access to dozens of productions from home. While outdoor theatre has long been commonplace in the summer months, we’ve also seen theatres think in new ways about how to put on shows in a Covid-secure way (such as a drive-thru production of English National Opera’s La boheme).

Now things are open, it will be interesting to see which – if any – of these trends are sustained, and if there are any changes to the types of productions put on. The arts certainly has an important role to play – not only in our financial recovery but also in helping us come to terms with what’s happened. In TV, we are beginning to see this: ITV’s Help starring Jodie Comer airs next week, tackling the topic of Covid-19 from the point of view of a care home worker.

Interestingly, Robert predicts no lasting change to the theatre landscape. “People talk about everything being different post-Covid,” he says, “but I’m not sure it will be. In the end it’s about finding something good and doing it well. That’s always been true and it will continue to be true.”

“In the end it’s about finding something good and doing it well. That’s always been true and it will continue to be true.”

For now, feel-good productions are leading the road to recovery. “After the time we’ve had, people want big, energising shows that are life affirming,” Robert said. “I’m sure we’ll see plays about the pandemic but right now it’s the high-energy productions that are doing best. Musicals in particular are proving popular.”

While they may not be as profitable, Robert and I discuss the importance of smaller-scale theatres, those off the West End or off-Broadway. “In a post-Covid world, theatres like The Royal Court, Donmar Warehouse and the Almeida are going to be more vital than ever,” Robert explained, “in this economic environment, they’re the ones that will be taking risks. They have what people call ‘the right to fail’.”

Robert reminds me that we are not yet out of the woods. He tells me that 40 productions have recently opened on Broadway but there are no tourists, upon which Broadway heavily relies. The West End has decided to go a different route and is opening up a little slower, which may be the answer.

I recently booked tickets to see Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem. The production isn’t on until next summer, and I hadn’t realised how much I’d missed the excitement of booking in advance and spending months in anticipation. For me, the lesson in all of this is the reminder to take nothing for granted.

Born? In Cuckfield in Sussex

Family? I’m married to journalist, Fiona Golfar, we have two children and I have three children from my first marriage – five all together and eight grandchildren.

What is your favourite production? The best thing I’ve ever seen was Michael Bennett’s original production of Dreamgirls. I first saw it when it was trying out at the Emerson Colonial Theatre in Boston, Massachusetts in the early eighties.

Who are your mentors? I’ve had many. Michael White is an incredible producer, and gave me my first opportunity to work for him. One of my fathers-in-law, Tony Richardson, was an excellent director and another mentor in a sense. Michael Bennett, director of Dreamgirls and A Chorus Line was another. And my mum!

What would you like your legacy to be? That I treated people fairly.

Moira.benigson@thembsgroup.co.uk | @MoiraBenigson | @TheMBSGroup