“No leader should be overly focused on today’s business – great leaders set their teams up to be successful today on the work they did years and months before, and look over the horizon to prepare for the future,” said Bill McRaith over Zoom, from his place in Scotland to me in my north London home. Last week, I had the pleasure of catching up with Bill, the former chief supply chain officer at PVH Corp., in order to congratulate him on entering what he is calling his ‘pre-tirement’ and reflect on his incredible career.

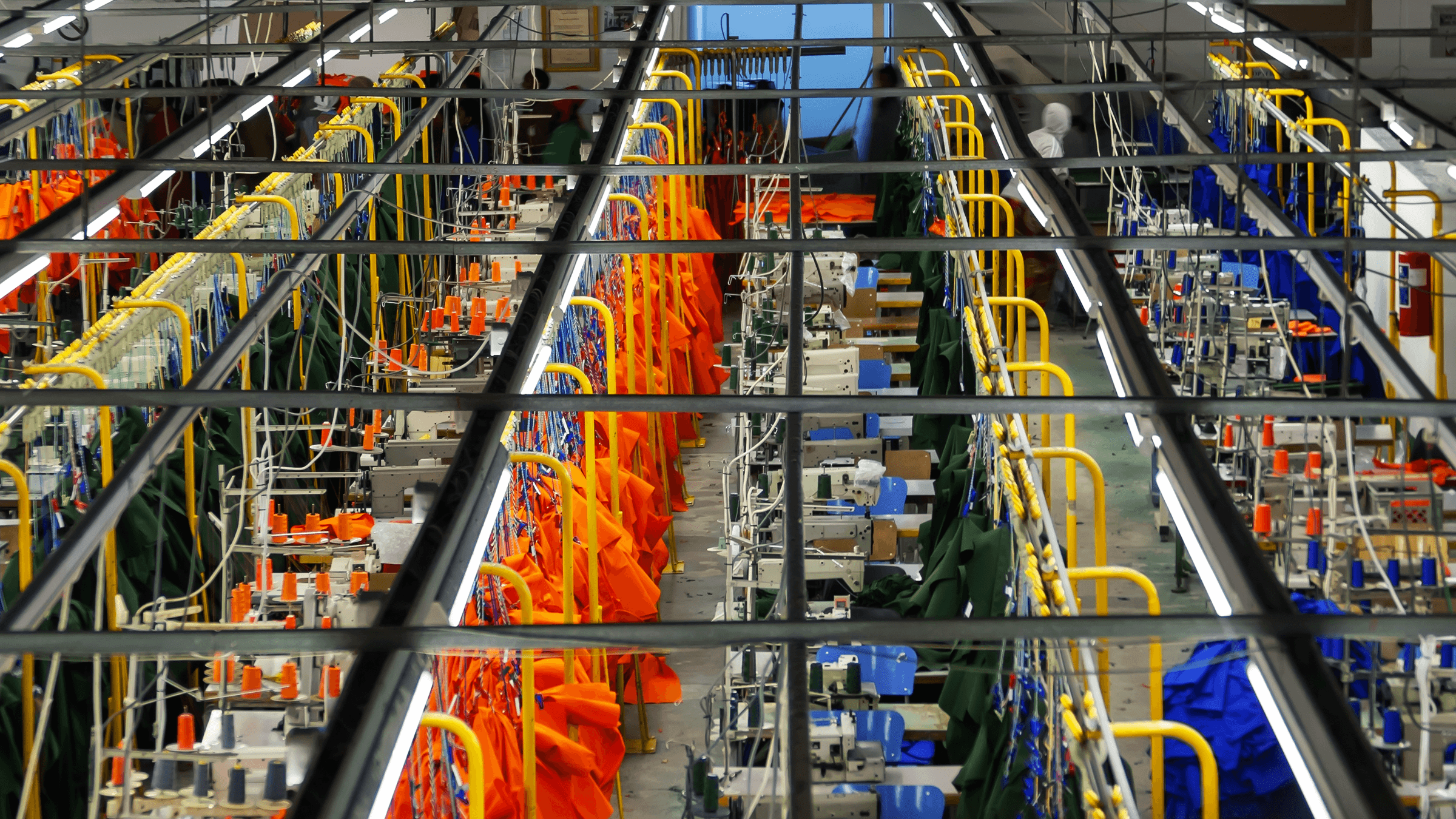

In his nearly forty-year career, Bill has certainly lived this value. He has witnessed – and been a part of – a magnitude of change in global supply networks. “When I started out in the apparel sector,” he told me, “everything that was sold in the UK was made in the UK.” Since that time, overseas manufacturing has exploded, and in 2020, approximately £20bn worth of apparel and clothing accessories was imported into the UK. Today, Bill is advocating for a new kind of model, a dynamic ecosystem, that combines offshore, nearshore and onshore manufacturing capabilities to eliminate planning waste, lower excessive inventories, increase responsiveness and profitability as well as encourage more sustainable practices.

Working around the world, Bill spent the first half of his career building some of the first real manufacturing capabilities in China, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and in South and Central America. “I met a lot of resistance,” he recalled, “from people in the US and UK garments and apparel industry who told me that countries in the developing world could never compete with UK manufacturing.”

The second half of Bill’s career involved leading supply network efforts for some of the biggest global retailers, including Walmart, Victoria’s Secret and finally PVH, which owns TOMMY HILFIGER and Calvin Klein. Moving into retail, Bill tells me, provided some much-needed insight into the challenges faced by retail leaders.

“As a manufacturer,” he laughed, “I’d always held the view that retailers were relatively unsophisticated… but when I joined the retail side, I realised that wasn’t the case. Retailers were dealing with an incredibly challenging trading environment, tough competitors and fickle consumers. Against this backdrop, they were making decisions that hindered the supply base without them even knowing.”

Bill tells me that, in moving from manufacturing to retail, he was able to bring the two sides together. “The problem was that each group didn’t understand each other’s challenges,” he said. “By getting them to understand each other, the value of a true partnership could be unlocked.” Bill is keen to define a partnership: “not as a transactional relationship, but as a true collaboration which is mutually beneficial.”

“The problem was that retailers and manufacturers didn’t understand each other’s challenges. By getting them to understand each other, the value of a true partnership could be unlocked.”

Over the course of his career, Bill has witnessed first-hand the evolution of the global supply chain network. “When I started my career, everything was local,” he explained. “There was no such thing as jetlag, no late-night calls with different groups around the world, we all spoke the same language. We understood the retail environment because we were shoppers as well as manufacturers.

“With everything made in the UK, there were no long wait times. When M&S would place an order with the UK-based company I worked for – Claremont Garments – the products were already made and sitting in our warehouse. So we could ship them in a couple of days, and then begin the cutting and sewing process to replenish that. There was very little work in progress and inventory in the system.”

Around about 1990, when he moved to China, Bill tells me, this simple and localised process was ripped apart as businesses realised the benefits of low-cost production overseas.

“But it didn’t rip apart equally,” Bill explained, “and for the last thirty years people have been trying to bring things back together.” With sewing outsourced to China and material staying local, businesses were initially faced with long lead times while materials were moved from Europe to Asia to be sewn. As time went on, material began to be produced abroad, by which point the sewing had also moved on to another location, and so on.

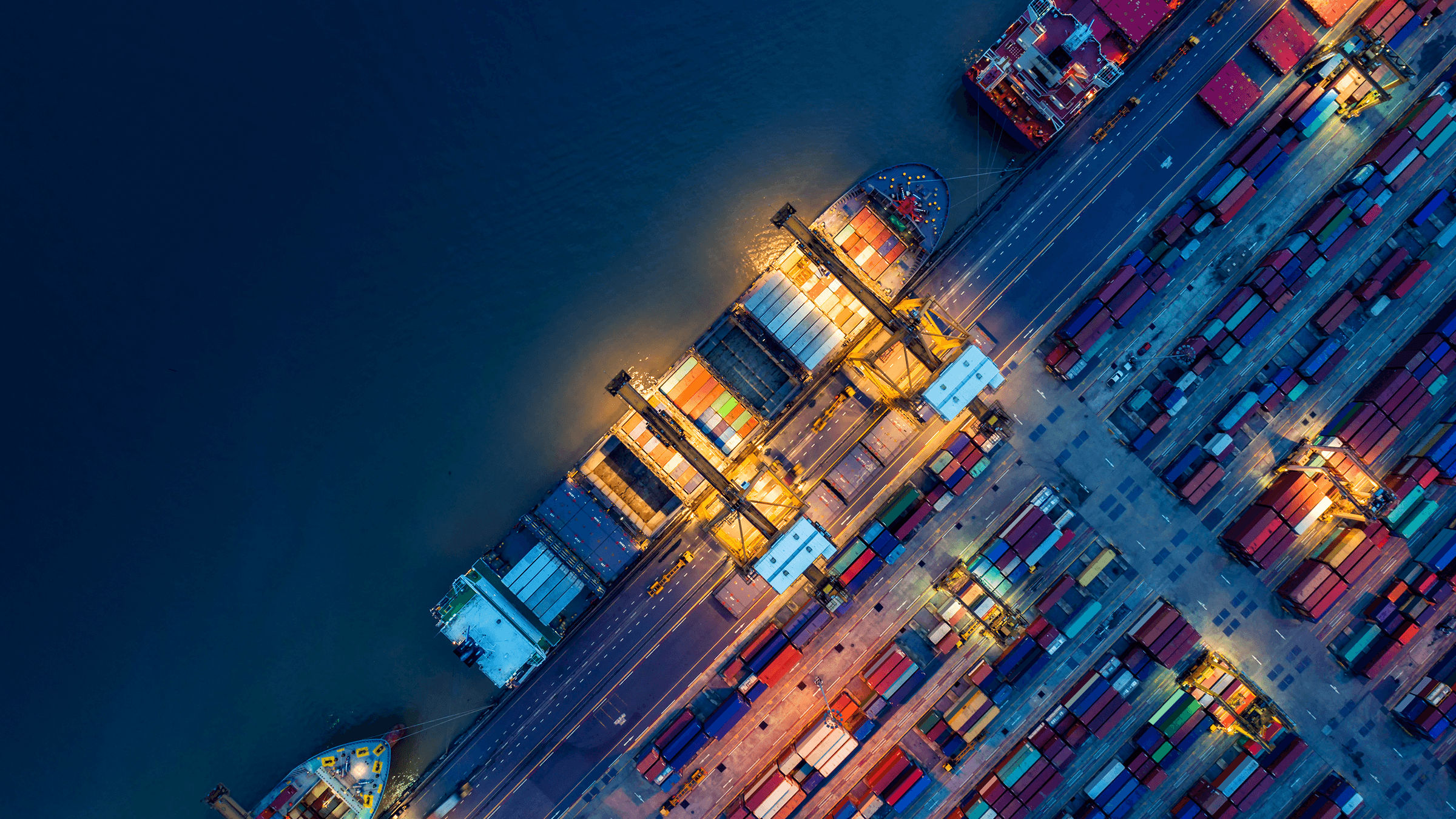

“We’ve spent the last few decades struggling to cope with extremely fractured and fragmented supply chains in which commodities, materials and parts are constantly moving around the world. This creates massive amounts of inefficiency, material and product waste, and generates a huge carbon footprint.”

Today, things are changing. More and more long lead times are damaging profitability and the cost of manufacturing abroad compared to at home is narrowing. In the last eighteen months in particular, Covid-19 has thrown the downfalls of a wide-spread global supply line into sharp relief. As international borders were closed, businesses with robust, local supply networks were often those that came out on top, at least until they were impacted by fragmented material flows. Moreover, consumers are increasingly becoming aware of where and how their products are made, and in some cases, seeking not only homegrown food, but clothes, too.

As he enters his ‘pre-tirement’, Bill is championing a new type of supply network which is not only more efficient, but addresses new retail, ecommerce, resale, circularity and consumer trends.

“What we’re doing now is what we should have done thirty years ago,” he explained. “We need to build our onshore capability back for testing new concepts, chasing styles and parts that can’t be replenished quickly offshore, at least without the damaging carbon footprint of airing goods. There are certain products that are highly predictable that can and should be made offshore, but those which are less predictable should be produced onshore or nearshore facilities, which can respond rapidly to peaks and troughs in consumer demand.”

The future of the apparel sector, Bill insists, lies in balancing onshore, nearshore and offshore capabilities. “It’s not that one trumps the other – it’s about building a dynamic ecosystem where they work in harmony with each other.”

“It’s not that one trumps the other – it’s about building a dynamic ecosystem where they work in harmony with each other.”

Looking ahead, Bill has some very exciting projects in the pipeline. His three priorities, he tells me, are “to stand back up apparel manufacturing capability in the UK, Europe and the US; the elimination and regeneration of waste; and cotton traceability.” Each of these initiatives has been on Bill’s agenda for years, “but I was spending a lot of time talking about it – and not a lot of time doing it.”

To round off, I asked him for his biggest learning. “If you want to change the way things operate,” he reflected, “identify the precompetitive opportunities and find likeminded organisations that can work together, from retailers and manufacturers to think tanks and political organisations. My success has been the recognition that no one person, retailer or supplier can change the world. Together we can!”

Quick-fire questions

Born? I was born in Kirkcaldy in Scotland, and went to Kirkcaldy High School.

Family? I’m married with three children, five grandchildren and a dog.

Favourite film? That changes over time! You become very patriotic when you leave the UK, so Braveheart sticks out – but I’m sure it’ll change again now that I am back.

Favourite book? My favourite business book continues to be Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t by Jim Collins. It was published twenty years ago, but the insights about good leadership and what makes a good company have remained true to this day.

Who are your mentors? I’ve had many mentors over time. One of the best was Glynn Manson, who first took me from the UK to Asia. He was a true entrepreneur and someone that helped me understand that you should always set targets way beyond your capability and fail forward. Don’t set targets you can achieve and congratulate yourself, set targets you can’t achieve and fail into them. Also Grace Nichols, who was CEO of Victoria’s Secret stores, was a true CEO who conducted the orchestra of everything in front of her.

What would you like your legacy to be? I want to be remembered as someone who looked over the horizon, and had the courage to lean into the pain of helping create the future supply chains, not simply recreating what already existed.

Moira.benigson@thembsgroup.co.uk | @MoiraBenigson | @TheMBSGroup