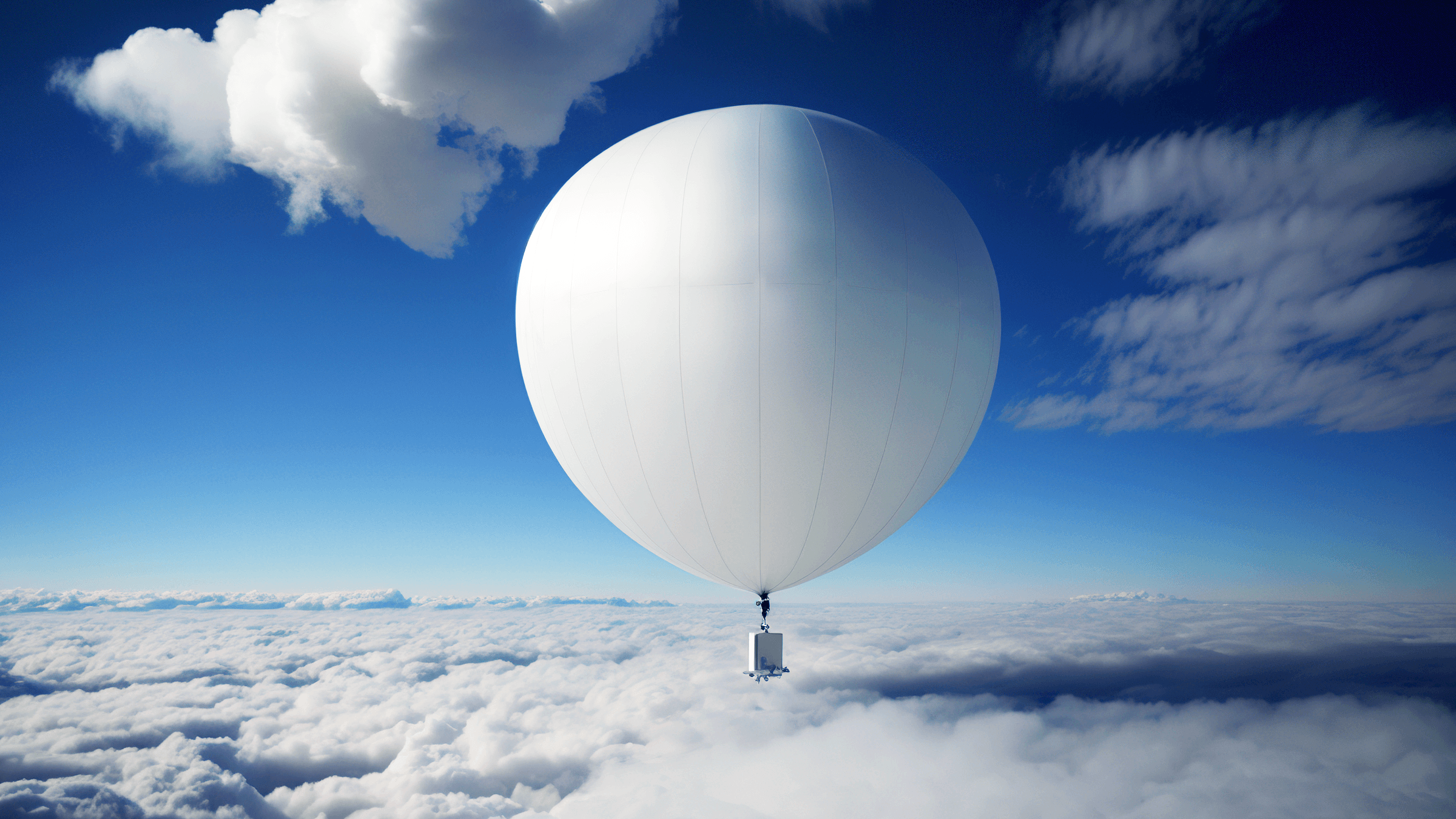

This week, news headlines were dominated by the US’s decision to shoot down a suspected 200-foot-tall Chinese ‘spy balloon’. Tensions are now running high between the two countries: China has called the US’s actions “indiscriminate use of military force” against a “civilian unmanned airship,” and the US Secretary of State has cancelled his visit to China. However protected we think we are from global politics, the threat of instability is never far away.

It is this notion that runs through Chip War by Chris Miller, an excellent book which details the decades-long battle to control what may just be the world’s most critical, and least well-understood resource: microchip technology. Semiconductor chips power everything from toys and cars to the electric grid and nuclear weapons – and are prevalent in nearly every aspect of our consumer sectors. In his excellent chronicle of the rise of the industry, Miller makes the case that our global economy and geopolitical stability are determined by who commands the chip supply line.

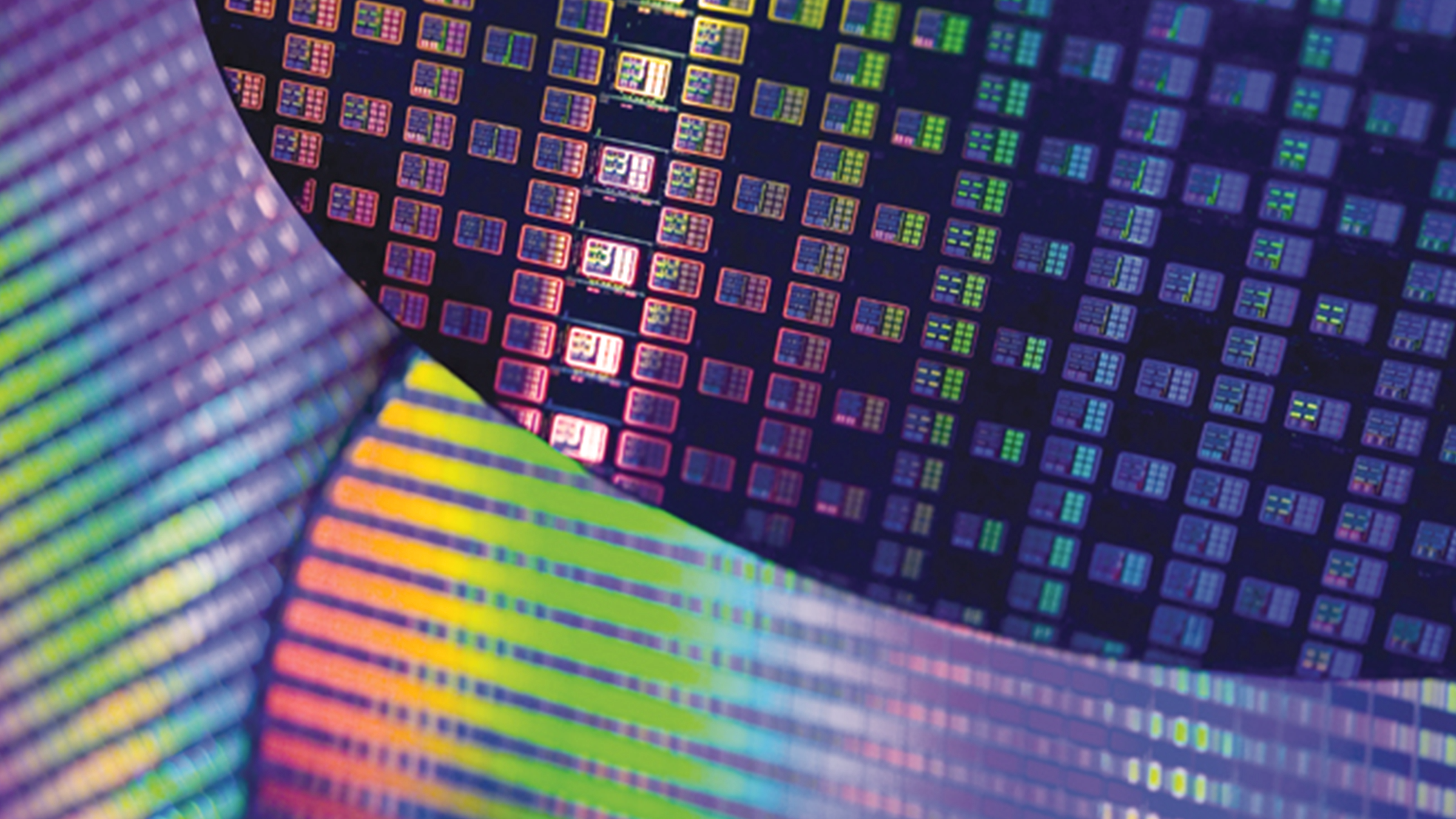

Until recently, the US designed and built the fastest chips – making them the historic chip “superpower”. Not anymore. Several decades ago, American manufacturers began offshoring their chip production to Asia, and now 40% of the world’s semi-conductors are made in Taiwan, with much of the Intellectual Property sitting outside the US.

It is an exceedingly complicated industry, and one that is developing rapidly. In 1965, chip pioneer Gordon Moore posited that the number of transistors on microchips would double roughly every two years. He dramatically underestimated scientific advances. Sixty years ago, four transistors could fit on a chip – today some 11.8 billion can.

Sixty years ago, four transistors could fit on a chip – today some 11.8 billion can.

The technology required to design and manufacture microchips could not be more complex, and depends on a very small number of businesses and state actors who now wield significant power. It is no wonder that earlier this week, the UK government intervened to try and ensure that Cambridge-based Arm Holdings – whose chip designs are used by more than 500 clients including Apple, Samsung and Google – to re-list on the UK stock exchange.

Recognising the importance of microchips, China now spends more on chip R&D than any other sector. The Asian superpower is pouring billions into a chip-building capability initiative to catch up to the US, hoping to challenge America’s military and economic superiority.

As Miller details in Chip Wars, chip technology is so important to China that the state-subsidised company YMTC – based right in the heart of Wuhan – was kept open during the pandemic, when the rest of the country was facing possibly the world’s strictest lockdown: “Trains passing through Wuhan carried special passenger cars specifically for YMTC employees, letting them enter Wuhan despite the lockdown,” he wrote. “China’s leaders were willing to do almost anything in their fight against the coronavirus, but their effort to build a semiconductor industry took priority”.

“China’s leaders were willing to do almost anything in their fight against the coronavirus, but their effort to build a semiconductor industry took priority”. – Chris Miller, Chip Wars

Chip War’s title therefore isn’t hyperbolic: if more than 40% of the world’s semiconductors are manufactured in Taiwan, then geopolitical instability in the region (in particular between China and Taiwan) would spell disaster for the global supply lines our consumer sectors depend on. Indeed, if the past year has taught us anything, it is that we can no longer rely on geoeconomic stability. Nearly all businesses will have experienced first-hand the ripple effects of Putin’s war in Ukraine, from severe delays in the supply chain to the hiked price of raw materials.

While measures are being taken by some companies to decrease dependency on Taiwanese-made chips – Apple recently announced plans to buy microchips made in a new Arizona-based manufacturing plant – how many businesses have any sort of action plan in place should Asia, in particular China / Taiwan, destabilise?

How many businesses have any sort of action plan in place should Asia, in particular China / Taiwan, destabilise?

The plans for a new Arizona chip factory have been hailed as an important step for American industry, but the plant will in fact be owned and operated by TSMC – the Taiwanese chip foundry that commands over half of global market share.

Across the world, it seems that many consumer businesses have become utterly reliant on technology that few understand, and even fewer have the ability to produce. It would be no understatement to conclude that microchips have become a foundations of our global economy, critical to the continuation of society as we know it. So why do so few business leaders fully understand them?

Most corporate risk-registers, rightly, focus on “known unknowns”. Naturally, Board discussions on risk tend to focus on agenda items where corporates can create viable contingency plans. However, in most businesses, items like chip dependency are rarely discussed – and, possibly, not even understood by some Board members. Deeper education and immersion in the end-to-end supply chain is key.

This is not to say that in the last decade Boards have not made significant progress into better understanding and regulating their supply chain. After much pressure from customers and increased media coverage, many brands today regularly audit their factories to stamp out child labour, unsafe practices, and environmental damage. These factory audits are hugely expensive and time consuming for companies to conduct – but have completely changed the operating environment in many countries, and enabled companies to deliver on aspects of their ambitious ESG goals.

But factories are just one element of the supply chain – and the most visible one. How many businesses have true oversight of their end-to-end supply network?

The shipping industry is a prime example. Shipping is bewilderingly complex by design, and often built on a Russian doll system of accountability. Aside from looking at the cost of containers, very few leaders actively scrutinise shipping operations in supply lines. But criminality, labor abuses, and environmental crimes are known to be rife within the sector (every year, for example, container ships spew about one billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the air – equivalent to 3% of all greenhouse gas emissions).

As companies struggle to find cost-effective ways to ship goods on time, how many take a step back and demand their shipping partners install more environmentally friendly engines? How many truly understand who owns the ships, taking the time to dig beneath the shell companies from whom individual containers are being rented? How many look at labour practices on-board the ships transporting their products?

Board oversight of supply chains is not easy. But too few Boards are in the dark about these key topics. Especially for businesses truly committed to ESG, ensuring a solid understanding of the issues at play is critical – but can be difficult to achieve without full oversight of ownership and practices.

To effectively lead an ESG agenda – and to mitigate risk – Boards need to educate themselves better about their end-to-end supply chain, including supply chain elements that are less than visible.

Geopolitical events like this week’s balloon escalation should give leaders in our consumer sectors sleepless nights. A geopolitical event in Asia between China and Taiwan could halt microchip manufacturing – which would spell disaster for many businesses in our sector dependent on chips. These issues are too important to “hope” against worst case scenarios. Increased knowledge of end-to-end supply chain may not give us answers, but it may well galvanise businesses to come together to think through contingency planning, and to address some of the unspoken issues. Ignorance shouldn’t be seen as bliss.

How well informed is your Board on its true end-to-end supply chain, and how often do these topics appear on your Board agenda?