In the past ten years or so, there has been a notable shift in the perception and power of Chinese brands. I grew up in mainland China, and I can still recall the excitement that swept through my school when Nike Air shoes became available to buy in local department stores. Wearing an international brand was to be part of the cool kids’ club; everyone wanted the Nike swoosh. But today, Chinese brands are gaining momentum on the world stage. The tables have turned, and now teenagers in the West are likely to be showing off their new clothes from fast fashion behemoth Shein, shipped all the way from China.

Chinese and east Asian brands are completely integral to the global consumer landscape. ByteDance-owned TikTok is now a household name, used by a third of the US population and nearly a fifth of all internet users. Last year, Shein raised $1bn in a round that valued it at more than Zara and H&M combined. And behind the scenes, the region’s manufacturing, logistics and technology capabilities are powering entire markets and categories across Europe, the US, Africa and the rest of Asia.

So how did we get here? In this column, I’ll take a look at how Chinese brands have gone global, and the challenges and opportunities they’ll face in the months and years ahead.

Perhaps most significantly, China still leads the way in manufacturing, accounting for more than a quarter of the world’s production output in 2021. The country has a long heritage of best-in-class production, having developed leading manufacturing infrastructure and workflow over the last forty years, underpinned by liberal labour patterns and a relatively cheap workforce.

For example, while laws stipulate that people should work for no longer than eight hours, overtime has become the norm in many settings, especially in factories. Chinese workers talk of the “996” regime, which refers to a work schedule of 9am to 9pm, six days a week. And when it comes to manufacturing technology, China is leading the pack: last year alone, Chinese businesses installed nearly as many robots in its factories as the rest of the world combined.

These factors have allowed China to retain its title as the world’s most prominent manufacturer. And over the past few years, Chinese brands have emerged to dominate the production of entire categories globally. Across Africa, for example, most mobile phones are made by Chinese firm Transsion. Sales in Africa account for nearly half of all revenue at the electronics maker. And if you own a drone, the chances are it’s made by DJI, a Shenzhen-based company founded in a dorm room in 2006. DJI makes three-quarters of all consumer drones, and today employs more than 14,000 people.

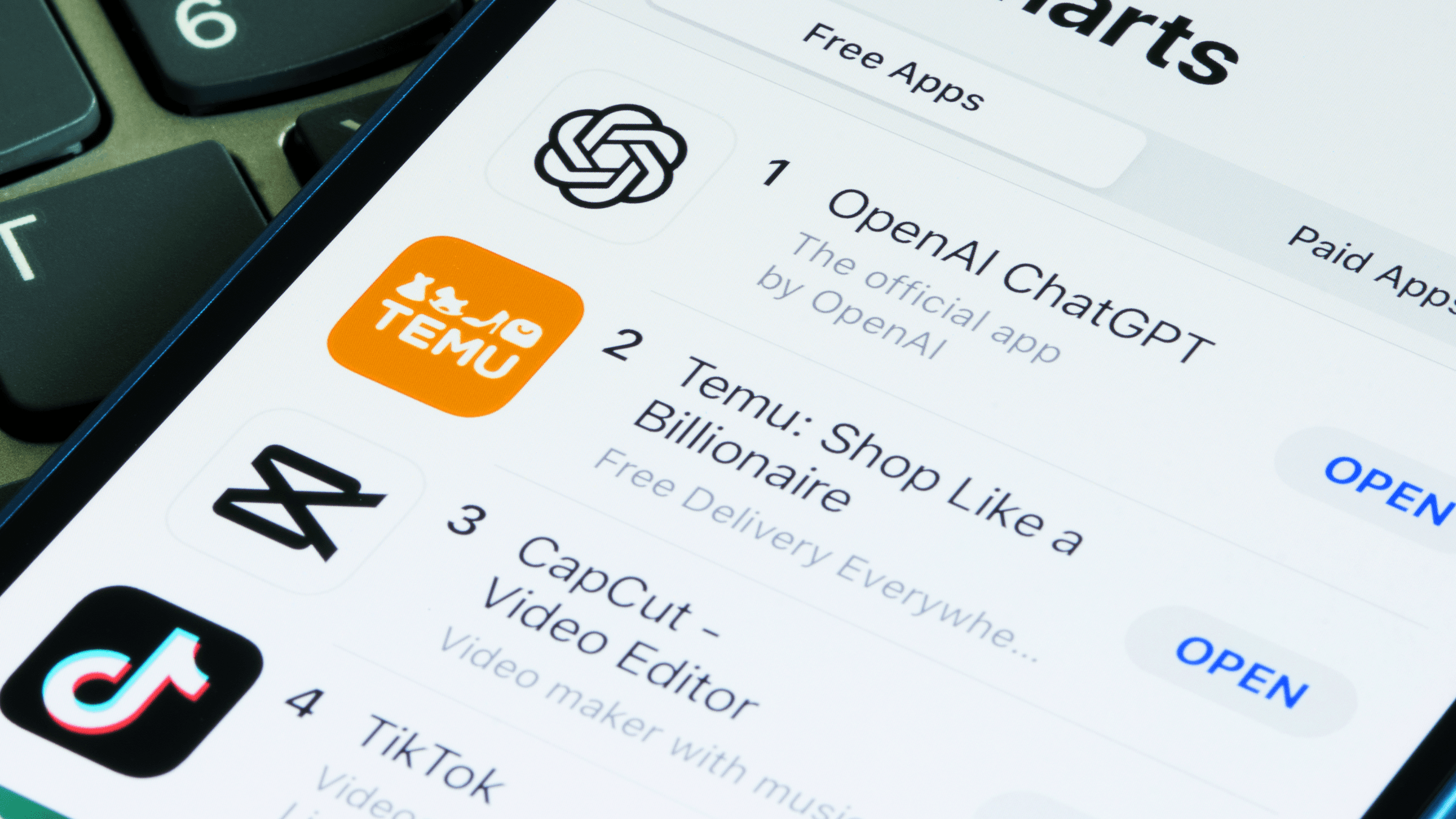

Turning to consumer tech, the past decade has seen east Asian firms become global innovators. Today, the influence of major players like TikTok (social media), Alibaba (ecommerce), Tencent (video games and messaging), and Grab (ride hailing) can be felt far beyond their home countries. And in the US, four out of five of the most-downloaded consumer apps are developed and published by Chinese companies.

“In the US, four out of five of the most-downloaded consumer apps are developed and published by Chinese companies.”

This impact is largely down to heavy investment in R&D. In 2022, for example, Huawei spent CNY161.5bn ($22bn) on R&D, representing more than 25.1% of total revenue. And at drone-maker DJI, a quarter of all workers are focused on innovation and development. The “super apps” also have best-in-class talent development strategies to drive sustainable growth. Alibaba’s Global Talent Development Programme aims to attract and develop leaders with expertise in cross-border ecommerce, big data and fintech to lead overseas expansion.

The rapid growth of Shein is perhaps the most visible illustration of China’s global influence. Founded in 2012, the business is now valued at $66bn (a dip from the $100bn it was valued at last year), and is changing the face – not to mention the environmental impact – of the fashion industry world-over.

Shein is pushing the boundaries of what is meant by fast fashion. Each item of clothing takes less than two weeks to get from concept to production, and once sold is sent in an individual parcel directly to customer doorsteps around the world. Design and manufacturing are provided mostly by third-party suppliers, and ordering decisions are powered by AI – custom software which identifies popular items and automatically places reorders, while halting production on products that aren’t selling. All of this takes place on a colossal scale: each day, Shein updates its website with an eye-watering 6,000 new styles.

While the company’s success speaks to its best-in-class logistics, it’s also a lesson in knowing your consumer – in this case, young buyers who are as driven by trends as they are constrained by budget. Shein’s marketing is powered by an army of Gen Z influencers, who are sent products and discount codes to share with their followers. Unlike other brands who opt for a more targeted approach, Shein’s strategy of working with a vast number of mid-weight creators has made it one of the most talked-about brands online.

What’s next? For some Chinese businesses, the future looks bright. Li Ning – which was born as a quality but affordable sportswear brand by the former Olympic gymnast Li Ning – is today making its mark in the luxury fashion arena. The brand showcased at Paris Fashion Week this year, with a collection described by its founder as “deeply and uniquely Chinese yet intended for all.” Those like me who grew up with the label are now strong advocates of its growth around the world.

But Chinese companies also face a raft of evolving challenges. Businesses are feeling the impact of growing scrutiny around working conditions and environmental impact. It will be interesting to see, for example, if Shein has a future in those markets which are taking sustainability and social governance seriously. In March of last year, the EU published its strategy for sustainable and circular textiles, in which the main objective is that all textile products on the EU market are “made [partly] of recycled fibres, free of hazardous substances, produced in respect of social rights and the environment” by 2030.

“Chinese companies face a raft of evolving challenges. Businesses are feeling the impact of growing scrutiny around working conditions and environmental impact.”

There’s also growing regulatory pressure and increasing geopolitical tensions. In November, the US banned the sale and import of new communications equipment from five Chinese companies, including Huawei, and just this March, the CEO of TikTok appeared in a US congressional hearing over concerns of Chinese government influence. Some businesses have taken steps to avoid being associated with China: TikTok now calls itself a “global company with HQs in LA and Singapore”, and parent company of ecommerce platforms Temu and Pinduoduo recently moved its head offices from China to Ireland.

Looking ahead, it will be interesting to see how Chinese businesses continue to leave their mark on our global consumer sectors. I’m excited to see what’s next, and how China-based companies adapt to, and improve with, the shifting consumer landscape. In my lifetime, the country has evolved from “the world’s factory” to a leading hub for innovation and new ideas, and maybe it won’t be too long before I can walk down a UK high street and see Chinese brands on the shelves.