August is a big month for football. The English Premier League kicked off last night, and in Australia, the quarter finals of the Women’s World Cup take place today. Against this backdrop, it feels like the right time to explore one of the most rapidly-evolving areas of the sport: finance. Clubs have long been valuable assets, sought after by individual investors, sovereign wealth funds, and other investment vehicles. But today, a new driver – namely private equity funding from the US – is making a lasting mark on the industry.

First, some context. Football clubs were originally not seen as profit-making ventures. The first instances of external club ownership can be traced back to the 1880s, when factory owners funded clubs from industrial UK cities in the north and the midlands, looking to elevate their home and attract workers through football. At this point, tickets were by far the biggest revenue stream, and any dividends were capped at 7.5%.

Fast forward nearly 150 years, and football clubs are commercial giants. The Premier League contributed £5.5bn to the UK economy last year – up from £2bn in 2010 – with clubs bringing in revenue through broadcasting rights, commercial sponsorships and merchandising as well as matchday sales.

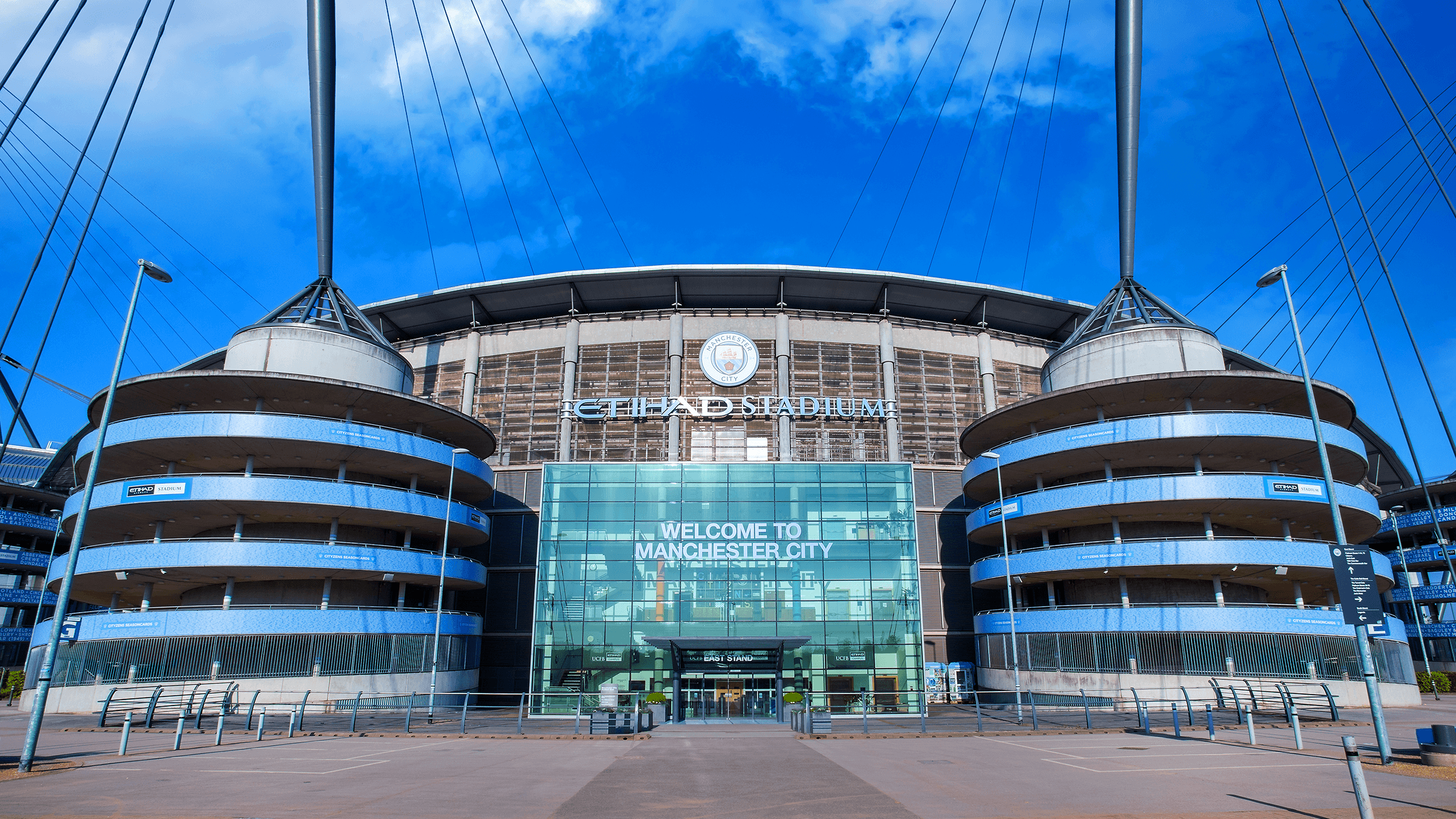

Overseas governments, especially in the Middle East, have been investing in the European game for years. As well as promising healthy returns, involvement in European football can be a way for governments to soften a challenging public profile. The most prominent example is The Abu Dhabi United Group, which bought Manchester City for £200m in 2008, before forming the City Football Group and taking stakes in 11 further clubs. CFG has propelled Manchester City to the top of the league (it currently holds three major trophies: the Premier League, FA Cup and UEFA Champions League), and invests heavily in local community projects.

The presence of funding from the Middle East has changed the financial landscape of European football. It has ramped up financial competition, sent transfer fees soaring, and paved the way for a “grow now, profit later” approach to operations. In the past two years, only four teams in the Premier League – Chelsea, Liverpool, Newcastle and Norwich – have made a profit. In turn, this environment has created prime conditions for participation from other forms of global investment.

“The presence of funding from the Middle East has ramped up financial competition, sent transfer fees soaring, and paved the way for a “grow now, profit later” approach.”

Today, private equity from the US is a major mover. In May 2022, Clearlake Capital made a $5.3bn acquisition of Chelsea, promising to revamp the stadium and grow the club’s profile internationally. Last September, RedBird Capital Partners completed a €1.2bn acquisition of AC Milan. Fortress Investment Group founder Wes Edens is a co-owner of Aston Villa, and Crystal Palace is part-owned by Apollo Global Management’s co-founder. The list could go on: according to a report from Pitchbook, more than a third of the top clubs across Europe have some level of private equity, VC, or private debt participation.

So why this sudden interest from PE?

For PE investors, football clubs represent valuable assets with steady growth trajectories. According to a Football Benchmark report, the aggregate enterprise value of the 32 most prominent European football clubs has increased by 96% in the seven-year period from 2016 to 2023 – a performance that outpaces the FTSE 100 Index.

Clubs’ growth is being driven by broadcasting and media rights. Currently, Sky Sports pays around £1.1bn per year for rights to show Premier League matches in the UK, a sum which is divided out by the league to participating clubs. In particular, the value of international broadcasting rights is spiralling, and Premier League clubs have been told that sales from overseas TV deals will overtake those from domestic contracts in the next three years. It’s the same story elsewhere in Europe: in Spain, for example, the rights to show La Liga matches for five years were bought by Movistar and DAZN for €4.9bn.

There are also new kinds of media deals to be made. As the way we engage with football changes, clubs can bring in sales through content partnerships with the likes of Amazon, Netflix or Apple. In 2020, for example, Spurs was paid £10m by Amazon for its behind-the-scenes docuseries All or Nothing: Tottenham Hotspur.

There are also structural benefits for PE firms. European football provides varied investment opportunities, including options for minority investment, providing debt, and the chance to buy out specific asses within one club, like its media rights.

This wave of private equity interest looks set to make a lasting impact on European football. On the one hand, PE firms are known for their long-term investment outlook, and will likely back projects that encourage sustainable growth, like infrastructure, training, and scouting high-potential junior players. Fixing dysfunctional cost structures is par for the course for PE firms, so it will be interesting to see whether private equity presence will wave in a more financially stable future for European football.

“Fixing dysfunctional cost structures is par for the course for PE firms, so it will be interesting to see whether private equity presence will wave in a more financially stable future for European football.”

On the other hand, many commentators have questioned if PE will make a wholly positive impact on the industry. We’re already seeing US firms use their collective bargaining power to apply pressure on European regulators, in a bid to build governance structures which drive clubs’ profit. Changes to financial fair play structures, salary caps, closed leagues rules and multiple club ownership arrangements may be on the horizon.

In many ways, this moment in football feels like the internet boom. Right now, everyone is scrambling for a piece of the pie – but the soaring growth trajectory won’t last forever. Broadcasting revenue looks set to flatline in the years ahead, and clubs and their owners must focus on creating new, diverse and sustainable income streams. For European football, the challenge is ahead is how to create a solid financial model which encourages growth – without losing the magic and cultural value of the game.