Patrick Kane’s email signature reads: he/him/disabled. “This isn’t because I want more time to complete tasks, or because I need reasonable adjustments,” he says, “but because when I solve a client’s problem, I want them to know that a disabled person did it.”

Patrick Kane is a Senior New Business Manager at VML, a published author, and an ambassador for The UK Sepsis Trust and for prosthetics developer Össur. After suffering from sepsis as a baby and losing some of his limbs, at 13, he became the youngest-ever person to be fitted with a bionic arm.

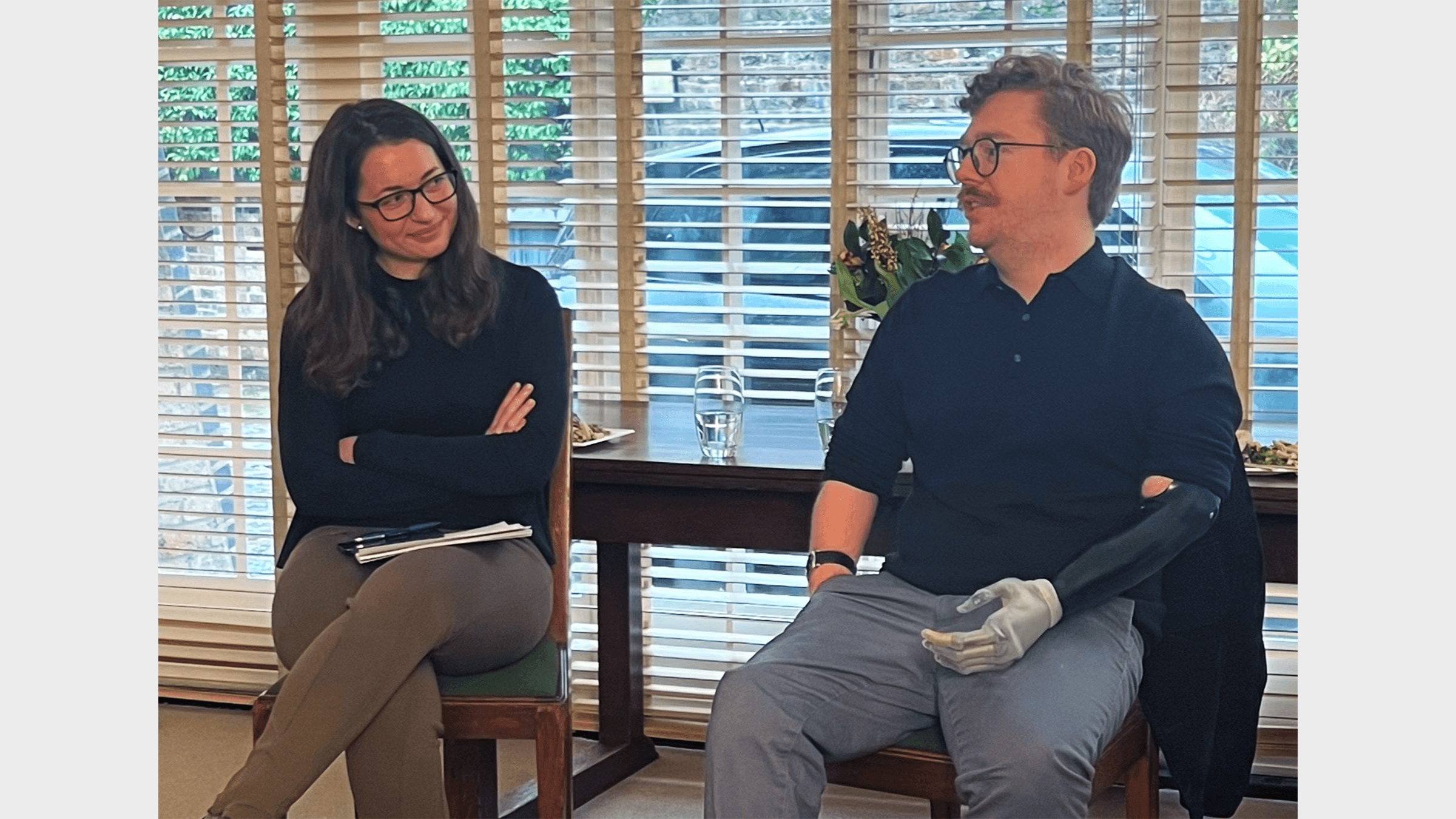

Last week, we had the pleasure of hosting Patrick for a lunch in our Primrose Hill office. Over the course of an hour, it was a privilege to hear more about Patrick’s experience growing up with prosthetic limbs, how his disability has positively impacted his life and career, and the ways in which he is advocating for a more accessible world for everyone.

“I was always told that if there is an elephant in the room, you should introduce it,” he began when we gathered together last Thursday. “I’ve got a prosthetic arm, a prosthetic leg, and I’m missing the second and third digits on my right hand.” Since he was nine months old, this has been Patrick’s version of normal. Throughout his childhood, he had a number of different prosthetics fitted, from a life-like cosmetic hand with limited function, to a leopard print-patterned leg. But otherwise, he tells us, his childhood felt unremarkable.

“I owe a lot to my parents – my mum and step-dad, and my dad who lives in Dubai – who gave me the freedom to make choices, make mistakes, and figure things out for myself,” he reflected. “I was never wrapped up in cotton wool, and never saw my disability as something that needed to be hidden.”

When he was 13, Patrick was fitted with a bionic hand. Now in its fourth generation, the prosthetic responds to movements in the forearm, the hand opening, closing, and gripping depending on different patterns of muscle activity. It’s certainly an incredible piece of tech, and one that afforded Patrick a new sense of freedom when it was first fitted in 2010. “It felt like the final piece of the puzzle,” he recalled. “For the first time, I could cut my own food and tie my own shoelaces.”

Patrick’s experience as an amputee has presented countless exciting opportunities: in 2012, he carried the Olympic torch at the London Olympic Games, in 2014, he spoke at TEDxTeen to improve education around sepsis, and now at VML, Patrick has established the global advertising agency’s first-ever disability-focused employee resource group.

But being an advocate for people with disabilities is far from his only – or even greatest – interest. “It’s just never been the primary issue for me, or what I’ve seen as my defining feature,” he explained. “It’s an intrinsic part of my life, but so are many other things.”

More compelling to Patrick is looking at accessibility through a broader lens. At VML, Patrick’s experience as a disabled person allows him to deliver projects that are more creative and more original in their approach. “Clients ask us how to make products and services better, and making them more accessible is a good way of thinking about that,” he said. “Ultimately, inclusive design is often just better design. The typewriter was invented so a blind person could write letters (which lead to the modern keyboard), and the touch screen was originally made for someone with mobility issues. These were accessible inventions that have become part of the fabric of society.”

“The typewriter was invented so a blind person could write letters, and the touch screen was originally made for someone with mobility issues. These were accessible inventions that have become part of the fabric of society.”

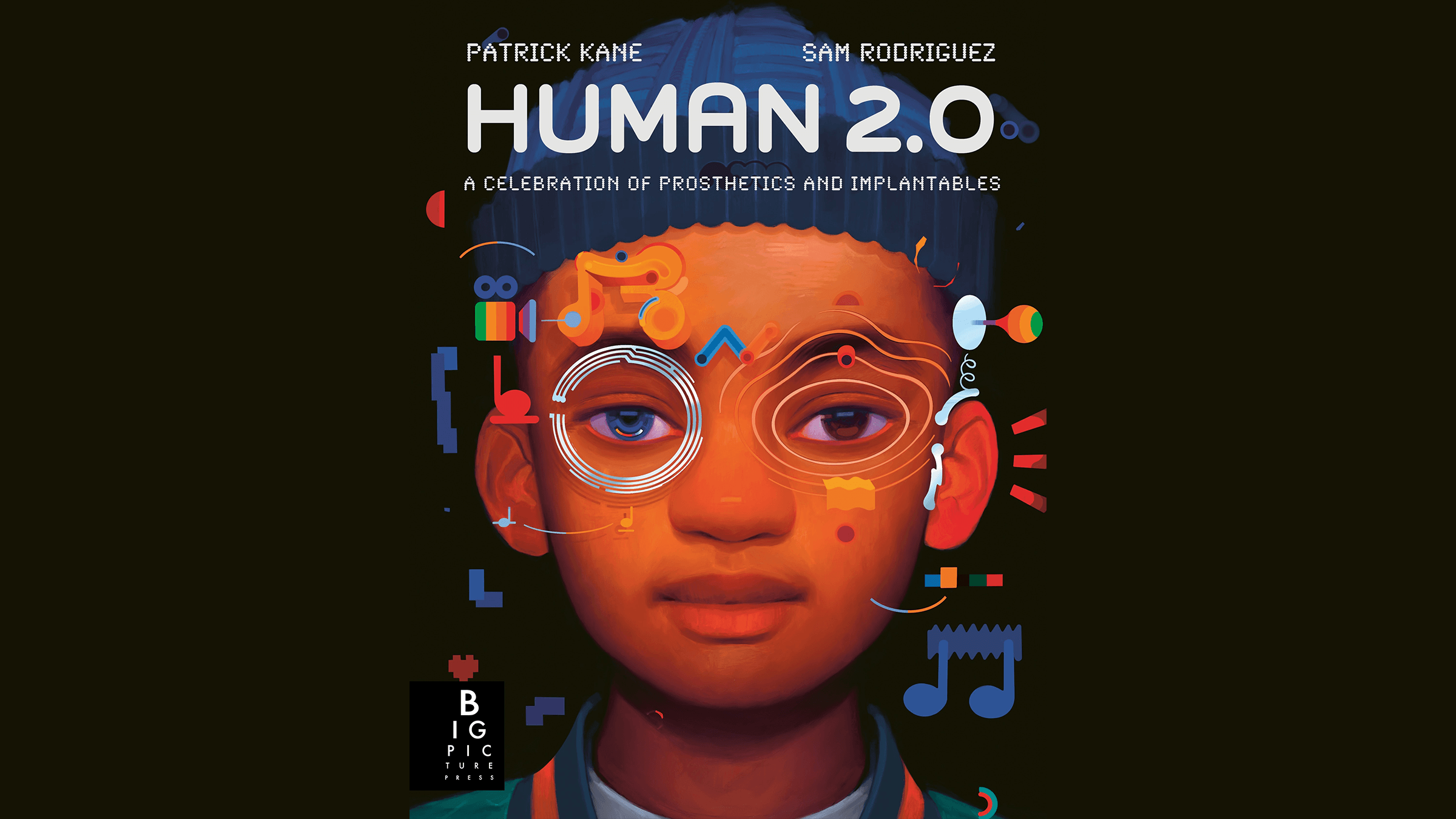

Indeed, as Patrick describes in his new book, Human 2.0: A Celebration of Human Bionics, some of the most forward-thinking innovations in medical and mechanical engineering today look set to make a broad-reaching impact. Patrick tells us about a current project underway at MIT’s Bionics lab: a pair of shoes that removes muscular strain when walking, making the activity 30% easier. While these shoes could prove invaluable for people with disabilities, they could also help anyone walk further, and for longer.

It is this notion of universality that makes the topic of accessibility so interesting. More than 80% of us will be affected by disability in our lifetime, and it’s something that happens almost inevitably with age. It’s also a very broach church, encompassing people with visible physical disabilities, as well as those living with chronic diseases, neurodiverse conditions and mental health issues.

It was interesting to hear Patrick reflect on his own relationship with the word ‘disabled’, a term which some reject for having negative connotations. “It’s a conversation I often have with other members of the disabled community, and I can see why it’s problematic,” he told us. “For a long time, I was adamant that I was an amputee, but that I wasn’t disabled. The word amputee described what had happened to me, without saying anything about my ability.

“Today, I think that the word disabled has become distanced from its original meaning of ‘not able’. It’s such a broad umbrella, and until there’s a better word – one that’s not patronising – I don’t see why we should try and change it.”

“Today, I think that the word disabled has become distanced from its original meaning of ‘not able’… I don’t see why we should try and change it.”

Another thing Patrick is clear on is that disability – in its most basic form of being ‘not able’ – is circumstantial and situational. “It is a mis-match between someone’s body and their environment,” he told us. Indeed, this idea is reflected in the updated definition of term disabled by the World Health Organization:

Disability results from the interaction between individuals with a health condition, such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and depression, with personal and environmental factors including negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social support.

To build a more accessible and equitable world, we must therefore focus on creating environments in which disabled people can succeed. In the workplace, this means providing reasonable adjustments and flexibility, and ensuring people are comfortable enough to disclose disabilities and ask for help where needed. “Hiring a disabled person is very different to retaining them,” said Patrick, “and it’s the employer’s job to create a setting in which that person can win.”

In the past decade, we have seen real progress on accessibility, in the workplace as well as in broader society. But there is still a very long way to go – and our afternoon with Patrick was an uplifting reminder of the broad-reaching benefits of living in a diverse world.

helen.benigson@thembsgroup.co.uk | liana.osborne@thembsgroup.co.uk | @TheMBSGroup